My colleagues and I, we work as Agile coaches. Every now and then new clients invite us to take a look at their Agile teams. These clients typically introduced Agile software development several months before, and they usually say that it was, in general, a good decision. They release more often with fewer bugs, changes to the products are made much more easily, customer happiness is increased, and so on. Yet we see also another picture: the client’s organisation and the client’s team are bull riding together.

From Bulls, Calfs, and Cows

Bull riding is a rodeo discipline, and the goal for the rider is to stay on top of the bull for a specific time. In this metaphor, who do you think is the rider, and who is the bull? A lot of people I asked said that the team is the rider and the organisation is the bull. What people who said that experienced is that their Agile teams are often crazy. We Agile coaches would call this behaviour hyper-productive, which sometimes seems scary or even crazy.

Even worse: What we often see is that the organisation is holding tight to or clutch firmly at the hyper-productive team full of energy. The organisation unleashed a force when they adopted Agile which collides with many organisational parts and patterns. The team just doesn’t fit into the organisational structure like the former project teams they had. It has needs and requests different from the ones the organisation was used to.

The organisation tries to strike back. Not only does it attempt to ride the bull, it attempts to rope the calf, to restrain it, to tie it down to fit in the organisational procedures. Calf roping is another rodeo discipline, where a mounted rider catches a calf with a rope, dismounts, and then ties three legs of the calf as fast as possible.

This is no fun for the calf. In organisations, every time a calf struggles figuratively against a rider’s rope, an Agile coach’s heart breaks. It’s just too sad to see an Agile team suffering because the organisational structure doesn’t allow him to be awesome.

What Agile coaches wish for Agile teams though, are happy cows on green meadows, perhaps in the Swiss Alps on a warm and cozy summer evening, with rainbows and everything. That’s an environment a cow is happy to be in and where it is the most productive. (Please don’t take this metaphor any further from this point on: We never said you should milk your employees or lead them to the slaughterhouse!)

The question for every organisation with Agile teams is: is there a way to build an environment as adequate to Agile teams as the green meadows are for the happy cows? Goods news is: there is a way. Bad news is: there’s a catch, too.

Theory X and Theory Y

Ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you think that people are unmotivated in general, that they don’t like working in your organisation, and that they wouldn’t work there if they weren’t treated with carrots and sticks on a regular basis?

- Or do you think that in your organisation people are self-motivated in general, that they do enjoy to work, and that they would work on their own even if there is nobody controlling them?

Douglas McGregor was a renowned management professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management in the middle of the 20th century. In 1960 he published a book called “The Human Side of Enterprise” where he defined Theory X and Theory Y. His assumption was that everyone within an organisation has an attitude towards two different directions, and he called Theory X and Theory Y.

Theory X describes people who believe that other people in general don’t want to work and that they have to be motivated extrinsically. Theory Y on the other hand describes people who believe that people in general do want to work and they motivate themselves (aka intrinsic motivation). It all breaks down to the central question: Do you trust your work mates that they’ll do a good job on their own, or don’t you trust them in this particular way?

Ricardo Semler is CEO at Semco and he got very famous for his Theory Y attitude. He describes the conflict between Theory Y and Theory X in his book “Maverick” as follows: “Workers are adults, but once they walk through the plant gate companies transform them into children, forcing them to wear identification badges, stand in line for lunch, ask the foreman for permission to go to the bathroom, bring in the doctor’s note when they have been ill, and blindly follow instructions without asking any questions.”

When we as Agile coaches see organisations struggling with their Agile teams, we ask the organisations about Theory X and Theory Y as a litmus test. The more they have a Theory Y attitude, the bigger their chances to create green meadows. Why? Because their chances are higher to create an environment where people experience flow during their work.

Flow

Flow is a concept in psychology, proposed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, psychology professor at the Claremont Graduate University, California, United States. He describes flow as “… a state of mind or a state of experience that we feel when we are totally involved in what we are doing.” It is the thin line where our skills and the difficulties to accomplish a task are in balance, which is called the flow channel.

Flow is the state of mind that organisations want their workers to reach when performing in their jobs. Why? Because when they don’t they work at an unsustainable pace, which may end up in a burn-out or bore-out. If the task is too difficult or the skills are too weak, people end up in anxiety. If on the other hand the task it too easy or there’s a mental underload, people end up bored.

In a company with Theory X believers it’s very unlikely to achieve a state of flow. That’s because when you don’t think that someone is willing to work, you end up controlling his work load, and when you do control his work load, it’s unlikely that you put him on that thin line called flow channel. (Well, to be honest, in every Theory X company there were almost always a few people working “under the radar” of their managers, at least from time to time. This way they were able to achieve flow states on occasion. Sad thing about this is: achieving flow should be normal, not an exception.)

What Motivates Us

To help their workers achieving flow, the best thing management can do is to create an environment which supports flow. Daniel Pink, author of the bestselling book “Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us” proposed three areas this environment should focus on:

- Autonomy: If you trust your people regarding work (Theory Y), than give them enough space so that they can balance their skills with their challenges.

- Mastery: With autonomy, you’ll release energy within your people which they in turn use to master their skills and become even better and better at work.

- Purpose: To direct the released energy, create a strong purpose (aka vision) which guides everyone in your organisation.

Usually when we explain this chain of reasoning, everything sounds plausible and understandable – at least for Theory Y believers. But that’s not enough for most companies. These ideas are just not tangible enough for them. They ask: “What specific steps can we take to create green meadows for our Agile teams?” And when we answered “There is no such thing as a recipe!” they kept insisting by asking “But what about some tips and clues how and where we could start?” At this point we came up with Agile Management Innovations.

AMIs

Agile Management Innovations are concrete practices to create an environment within organisations to support Agile teams. AMI is our abbreviation for Agile Management Innovations. It’s pronounced like Amy Farrah Fowler from The Big Bang Theory or like the great singer and songwriter Amy Winehouse: AY-mee. And if you now think “My, that sounds lovely!”, then this is not an accident, but by intention: Amy means “beloved”.

We collected 26 different AMIs over the last years, and we have hands-on experience with all of them. We use them in our own company it-agile, and we help our customers to use them in their organisations, too

The term management innovations originates in the book “Management Innovations” by US-American management expert Gary Hamel. According to him, management innovations are “… anything that substantially alters the way in which the work of management is carried out, or significantly modifies customary organisational forms, and, by doing so, advances organisational goals.”

The reason for us to call it “innovations” and not e.g. “practices” or “techniques” is, that in our experience 50 % of the way an AMI is established in a company depends on the company culture. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”, management guru Peter Drucker stated a long time ago, and that’s the reason why we see AMIs as impulses and inspirations for organisations searching for ways to establish green meadows. AMIs are not step-by-step descriptions of foolproof procedures. That’d be Theory X thinking. In true Theory Y attitude, AMIs are real-world examples served as food for thought and triggers for change.

Our Management Innovations are Agile, because, as in Agile itself, AMIs are focussed on the people, i.e. more on “individuals and interaction” and less on “processes and tools” like the Agile Manifesto states. People with an Agile mindset trust their work mates. They help to create green meadows, which illustrates this principle, which was also written in the Agile Manifesto: “Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.”

There are 26 AMIs so far, clustered in 6 categories:

Money

- Open Books: Business figures are accessible by employees, and employees are trained to understand these business figures.

- Open Salary Structure: Particular case of Open Books, where employees know each others’ salaries and are able to reference them in a company wide context.

- Profit Sharing: Employees are substantially benefitting from the companies profit.

- Peerbased Salary Determination: An employee’s salary is determined by peers chosen by the employee.

- Salary Self-determination: An employee’s salary is determined by themselves.

Collaborative Infrastructure

- Organisational Retrospectives and Retreats: All employees of an organisation frequently gather to reflect their past, plan their future, and connect to their present.

- Open Space Technology: Meeting form to exchange ideas and connect people without having a formal agenda.

- Slow Communication: Way of communicating asynchronously to have more uninterrupted flow moments.

Teams

- Team Empowerment: Teams are autonomous, self-organised and cross-functional.

- Sociocracy: The organisation is partitioned in teams and decisions are made via Konsent (see Konsent in category “Decisions”).

- Happiness-Index: A niko-niko calendar is used to measure happiness within a team and company wide.

- Reverse Accountability: Managers are accountable to employees.

- Hiring through Team: Fresh engagements are hired and dehired by the team.

- No Job Title or Description: Employees don’t have job titles and job descriptions.

Decisions

- Konsent: Form of decision making within teams or whole organisation where a decision is made when nobody has a reasoned veto.

- Concrete Experiments: Changes to the organisation are made with concrete experiments including a specific time to run and a hypothesis the outcome can be compared to.

- True North: A range of unreachable goals helps the company to channel energy by having a direction.

- Simple Rules: A minimal set of rules instead of a huge amount of documented instructions to make regulations within an organisation.

- Delegation: Clarification of the level of delegation is essential for collaboration.

Mastery

- Peer Feedback: Employees have peer groups which give regular feedback on the employee’s performance and help him or her on their further journey.

- Mentoring and Coaching: Mentors help employees to find their next career steps, and coaches help employees to grow personally.

- 360 degree evaluation: This is feedback trough the wisdom of the crowd. All of the company’s employees give small feedback to everyone they know in the company.

Customer and Innovation

- Slack: Work time in which an employee is free to work on whatever he wants.

- Work on Sight: Every employee has contact with the customer.

- Innovation Days: Time span in which the whole organisation concentrates on creating concrete innovations.

- Net Promoter System: Having a tight feedback loop with the customers about products and services.

Let’s dig a little deeper into the following 7 of the aforementioned AMIs. Not only will we explain them to give an impression about how we see AMIs, but we will also give some advice for a few of them as to how an organisation could introduce them.

Slack

Slack is the idea of allowing employees to work on whatever they want, no strings attached. Companies like Google made this concept famous. Instead of trying to optimise utilization, Slack supports autonomy. Within such an autonomy, every employee is able to follow their energy without constraints. Often the results are very innovative concepts and ideas, usually accompanied by an immense amount of learning by each individual with further or advanced training.

Famous companies used and use slack: 3M invented the Post-it notes within slack, and so did W.L. Gore and Associates with their waterproof and breathable fabric Gore-Tex and the amazing Elixir guitar strings. Google’s online mail service GMail, Google News, even Google Agile programming, all started within slack time of their employees.

3M, Gore and Google offer their employees to spend between 10 % and 20 % of their work time on slack. We at it-agile give our employees 30 days of slack every year. The outcomes are numerous. AMI, both idea and concept, was for example invented partly in our slack.

It’s very easy to introduce slack within your organisation: just start experimenting by giving your employees 1 day of slack per month.

Konsent

Konsent (yes, with a k) is a form of decision-making. You can try it even in small teams. Instead of having a majority voting, konsent is reached when everyone is in agreement with each other. With every majority-voting, as long as it’s no consent, there’s always a minority. It’s hard to act in concert if there’s at least one in the group whose vote was overruled. In a konsent, everyone’s acting in concert.

In a consensus everyone has to be in favour of the motion. In a konsent no one must be against the motion. That seems to be a small difference between consensus or consent (with a c) and the Dutch word konsent (with a k), but yet it’s a huge leverage considering the impact it has on the decision to be made.

Consider a team agrees to make decisions via konsent. When a point comes up which needs to be decided, someone proposes a motion. The team then does a procedure called thumb voting, which is often used in combination with konsent. Using their thumbs they indicate three states to each other:

- Thumbs up: I’m in favour of this motion. I’ll commit myself to it and I will stand up for it.

- Thumbs aside: I’m indifferent and might not be particularly fond of it, but if this motion is accepted, I’ll support it.

- Thumbs down: I’m against this motion and I veto. My reason for my veto is X.

The last part, the veto, is crucial. When someone gives a veto, he has to come up with a reason for it. The other team members can then work with that reason, e.g. trying to alter the motion so that the vetoing team member could change his position in the decision making process, i.e. changing his thumb down to a thumb aside. Every veto is a chance to attain a better or higher motion than it was before.

True, konsent is sometimes harder and slower to achieve than a majority voting, but only at first sight. If you have an overruled minority after a majority voting, that minority might attack the decision whenever there’s an opportunity. Depending on the success of these attacks, majority voting can lead to long-lasting unresolved decisions. On the contrary, konsent means, that if once established, everyone acts in concert. That is because everyone was – thanks to the possibility of a veto – heard before the decision was made.

Open Space Technology

Open Space Technology (short: OST) is a form of a meeting, or to be more precise, a form of a conference. Such a meeting or conference is called an open space. At it-agile we do open spaces several times a year, company wide and also within smaller groups. We use it at our customers all the time, sometimes even in trainings.

An open space usually lasts between half a day and 2 days, and it has no agenda. There’s an inspiring and guiding theme for the whole meeting like “How to tune our company?” so every attendee will know what the open space is about. Open spaces are moderated by an experienced host who facilitates the attendees. He takes care of the meeting process so that the attendees can concentrate on what matters most: communicating with each other.

The agenda is built by the attendees at the beginning of an open space. Everyone who wants to share something he knows or wants to know about or just wants to exchange thoughts about something writes his session title onto a card together with his name as the session host. The name is needed for the attendees to know who the session host is.

In a format called “market place” every session is described shortly by the session host. He finds a spot on the agenda. This is being repeated with all potential session hosts until the whole agenda emerged with the usual grid with tracks and times you can find in any conference program. (Beware: While a lot of public conferences with an open space part have a market place, they lack of a profound closure where the participants agree on further actions.)

Harrison Owen, the originator of OST, distinguishes OST from any other conference format by applying the following 5 principles and 1 law:

- Whoever comes is the right people.

- Whenever it starts is the right time.

- Wherever it happens is the right place.

- Whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

- When it’s over, it’s over.

These 5 principles are not meant to control but rather to describe the process

“Law of Two Feet” is what the only law for OST is called by Harrison Owen, and it states that “…if at any time you find yourself in any situation where you are neither learning nor contributing – use you two feet and move to someplace more to you liking.” See it that way: if you’re not learning or contributing, honour the participants of a session with your retreat.

Compared to slack or konsent, open space needs more preparation and a good moderation by an experienced facilitator. It is therefore a little bit harder to experiment with than slack or konsent. I’m continuing to slowly increase the degree of difficulty when introducing AMIs with the next one.

Mentoring and Peer Feedback

Mentoring and Peer Feedback are actually two different AMIs, but they are closely related and on the surface of this overview similar to each other. Mentoring means that every employee has the chance to chose a mentor in the company. A mentor is someone who has already been where the mentee wants to go, and he’s therefore able to guide the mentee on her way.

Peer Feedback, on the other hand, is what a peer group can give to a colleague. It’s an alternative to a top-down feedback that a boss would give to his underlings. A peer group at it-agile consist of at least 3 different colleagues. Our peer groups are cross functional, i,e. there’s at least one consultant and one developer in the peer group.

(At it-agile we once thought hard about a name for the role of an employee who has a peer group. There were funny and sad names, like “peee” (“A mentor has a mentee, so a peer group has a peee?!”) or “victim” (yeah, we didn’t like that one very much). One guy, I forgot who it was, said with a warm and caring tone “sheep” – and this somehow got stuck in the company.)

Organisational Partitioning

Sociocracy was originally designed to be a system for governance, but is today used by all kinds of organisations. There are two main practices in a sociocracy: decision-making by the aforementioned konsent and what we call organisational partitioning in teams. Organisational partitioning means, that every single employee in the company is part of just one team. All the teams are linked to each other in a way which provides learning from each other while having a great scale of autonomy.

There are several well renowned companies using organisational partitioning: Handelsbanken is a highly decentralised Swedish bank, where each branch acts like an autonomous team. Whole Foods Market is a US-American foods supermarket chain, where the basic organisational unit is not the store, but the team (of which a store has several). Our own company, it-agile, is completely divided into teams.

it-agile’s teams have a huge scale of autonomy, but, on the other hand, have a big deal of responsibility, too. Each team is responsible for

- Customer satisfaction

- Employee satisfaction

- Economic viability

- Usefulness for the whole company

- Recruiting and decruiting

Sure, organisational partitioning is a very sophisticated setting for a company. You might want to start little by just having one team. Then, success presumed, add another team and figure out how to deal with the interactions of two teams. Add another team, and another, until everyone is in a team.

Open Books

Open Books means not only every business figure in the company is available for every employee, but every employee is also able to find them on her own and is able to read and interpret them. Why? Because if you see the idea of self-organisation and autonomy as valuable, open books are very helpful. They allow teams and individuals to much better figure out ways to improve their work and to take responsibility for their own actions.

For example, do you remember the aforementioned responsibilities of it-agile’s teams? One of them was “customer satisfaction”. We once had developers and consultant who didn’t know what the customer paid for their services or what deals exactly the customer made with our sales persons. After we made our deals with the customers public within the company and explained how to read and interpret them to everybody, our consultants and developers started giving tips to the sales people regarding things to improve. This behaviour resulted in better processes and in more satisfied customers.

Another, more strange example at it-agile is our open salary structure, which is another AMI. It’s a special case of open books. Since payroll costs are the biggest part of our overall costs, how could our teams be responsible for economic viability without being able to know their salaries?

Profit Sharing

Profit Sharing means that employees substantially benefit from the company’s profit. You have to search a long time to find companies doing that. For example in Germany the common share for all the employees in a company with profit sharing is 5 to 10 % – the rest is for the shareholders. We don’t call that a substantial amount. Even worse, in Germany only every 10th company does profit sharing at all.

At Gore, every employee is a stakeholder. After their first year, they can have 12 % of their salary in form of stocks. At Semco, the ratio is even better: dividends and stakeholders get 25 % profit share, employees 23 %, rest goes to taxes (40 %) and reinvestments (12 %). Semco’s employees decide how they want to split their 23 %; so far, their share is splitted evenly, so every employee got the same amount. At it-agile, 25 % goes to our stakeholder, 12 % goes to our founders, and the rest of 63 % goes to our employees, where it is evenly splitted.

Those are examples of more or less substantial amount. By substantial we mean that employees should have a significant share, not just a symbolic one.

One of the main reasons the employees at it-agile participate in a self-organising way and want to handle the responsibility of economic viability and hiring is our profit sharing. Every employee, even our general managers, have the same share of our profit (we’re talking amount, not percentage!). That means that every employee knows exactly that spending and earning money has direct consequences for her own share. Nobody would say “Well, it doesn’t matter how much it costs. The company will pay for it!” The company is the people. Everyone would pay with their own money.

Now we explained a few AMIs and how you could start using some of them right now. There’s a general principle we’d recommend to you when you want to apply AMIs to your company: let your employees chose whether they want to be part in an AMI or not. And trust their choice.

For example at it-agile, peer groups and mentors are being chosen on one’s own free will. Nobody has to have a mentor, and if one doesn’t want to have a peer group she can go back to receive top-down feedback from one of our general managers. No team is forced to make decision with konsent either. Each team decides about its own decision making process. In some AMIs voluntariness is already build in: Open Space has a built-in-voluntariness: the “Law of Two Feet”.

Pull

This principle is called the pull principle, since it does not push assignments, but offers choices to pull. Bill Gore, founder of W.L. Gore and Associates, put it this way: “Authoritarians cannot impose commitments, only commands.” We highly recommend that when you make use of AMIs, remember not to push them, but let your people pull them.

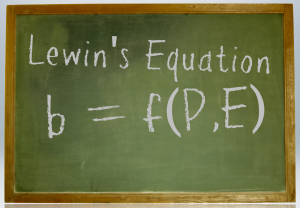

Lewin’s Equation

You’re ready now to create green meadows, i.e. environments compatible with Agile values which suit your Agile teams. Creating an environment is actually a very smart thing to do. Kurt Lewin, a German-American psychologist, was a pioneer on the field of social psychology. The so called Lewin’s equation looks like this: b = f(p,e) What it means is, that the behaviour b of a person p is the function of the person and his environment e. Combine this with the idea that nowadays every psychologist and coach knows: You can’t change people directly in order to change their behaviour. What do you get? Right, you can only change a person’s behaviour when you change their environment.

If you do, immediately give up trying to change persons directly! Instead, make participating in AMIs optional. Think about green meadows and concentrate on the environment in order to change the behaviour of people. All AMIs are focused on changing the environment, and the pull principle prevents people from over-eager managers who can’t wait to see different behaviour fast enough.

How to Start with AMIs

How should you introduce AMIs? We recommend considering what we call management experiments. Experiments are the only way to manoeuvre in complex waters, and a company with it’s employees is a very complex water (cf. complex domain in the Cynefin framework). Experimenting means that you are limiting the risk of the impact of an AMI by doing small steps one at a time. Start by looking for a problem you want to solve. Then choose an AMI (or invent one of your own) which might address this problem. Consider that you can’t be sure that your problem will be solved by that AMI, since in a complex environment you don’t know all the effects in advance, only in retrospect.

After you have a problem and an AMI which fits to that problem, don’t plan the big transfer for everyone. Ask for a few volunteers for this experiment. When you want to try out decision making with konsent for example, ask for a single team which was uncomfortable with their current decision making wants to be part of that experiment. That’s enough volunteers you need for now.

Specify what you want to learn by the experiment and come to an agreement regarding the amount of time you need to learn this (e.g. 3 months). Then start the experiment. After the 3 month time box is over, evaluate the experiment and either discard the AMI (and try another one) or expand the experiment, e.g. to more than the original team. Eventually integrate the AMI in your corporate culture.

Let me make this absolutely clear: There is no other way to work with AMIs than with trial and error. There is no big plan or blueprint for success when it comes to management and people. No one can predict the outcome of an AMI in different corporate cultures, since we’re all individuals, and that includes the employees in your company, too. That’s another reason why we don’t see AMIs as practices, but merely as impulses and inspirations.

We wish you a nice journey towards green meadows and happy cows! Moo!

(Thanks to my team, i.e. Ilja Preuss, Sandra Reupke-Sieroux, Florian Eisenberg, Christian Dähn, with whom I have the honor to work with at it-agile. I deeply appreciate your support and passion regarding AMI. You guys rock!)

tl;dr

AMIs are impulses and inspirations for companies eager to change their environment in a way that is compatible with Agile methodologies. We identified 26 AMIs so far in different categories like money, decisions, teams, etc. AMIs allow employees to experience more flow, self-responsibility and self-organisation by fostering autonomy in a structured way. We recommend making participation in AMIs optional (pull principle) and on a time boxed trial and error basis (management experiments).

Pingback: Agile Management Innovation and Culture Hacking at LESS 2012Jason Little | Jason Little

Pingback: Agile Management Innovations: Voraussetzungen für mehr “Flow” schaffen - //SEIBERT/MEDIA Weblog

Pingback: LAST 2013: Inspire Management | Ruma Dak's Blog

Pingback: 42 Tasks for a Scrum Master’s Job » Agile Trail

Pingback: Das Digitalisierungs-Management-Dilemma

Pingback: Agile Organization: Hackathons at //SEIBERT/MEDIA | News, tips & guidance for agile, development, Atlassian Software (JIRA, Confluence, Stash, ...) and //SEIBERT/MEDIA

Pingback: Scrum Master'ın 42 Görevi

Pingback: Cosas a realizar en el trabajo como Scrum Master – marcoviaweb